An insider's tour of London’s anarcho-punk spaces, tracing the squats, venues, and communities that made resistance possible.

- david1170

- Jan 3

- 6 min read

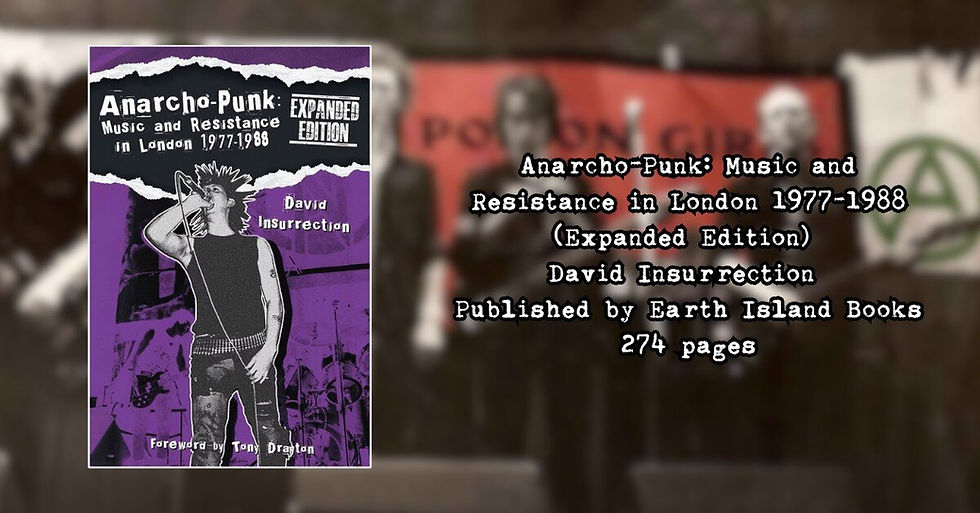

The original edition of this book about locations in London associated with anarcho-punk came out over a year ago. In this new expanded edition, David Insurrection has added 15 chapters, some more photos, and additional material in some of the existing chapters to boost this book by 50 pages, and it instantly looks more weighty. Luckily, this fascinating study is still not as big as an Ian Glasper title, so there’s no need for heavy lifting gear.

Anarcho-Punk: Music and Resistance in London 1977–1988 takes a meander through sites with a connection to the vibrant anarcho-punk scene of London in the 1970s and ’80s. There is no discernible order to the content, with the book jumping about, although there are a few clusters of chapters, such as those focusing on Hackney squats and housing co-ops. Each chapter exists in its own right, so you can dip in as any particular site piques your interest. As David sets out in the introduction, you can use this as a guidebook if you want to do a DIY tour of places that “once were.” What would have been really interesting is a map showing the distribution of sites, but that just couldn’t fit onto the pages and remain legible at the same time.

In the 1980s bands like DIRT, Crass, Conflict, Flux Of Pink Indians, The Mob, Zounds, Rubella Ballet, Hagar The Womb and a host of others could be seen at a variety of venues across London, and punks from the provinces flocked to live there in free or cheap housing. This book features a healthy smattering of houses occupied by housing co-ops and squats where these incoming punks lived, in addition to music venues. Yes, it’s couched in terms of “famous” band members or zine writers who lived at these locations and wrote or rehearsed there, but we get a feel for the space that allowed every day rebellious punk rock existence in the ’80s.

The venues were quite often squats, the reasoning summed up by Nigel from Sterile Records “When venues aren’t available, you take the DIY approach. That has always appealed to me, both politically and practically. I never wanted much to do with the business side of the music industry. The people I met there didn’t appeal at all. I found it nauseating. So I took a direct route and I still do.” Our author takes us on a tour of the sites of these locations, some like the Zig Zag going down in punk folklore.

Wanna know what punks can unleash if let loose in a falling down building? It’s all in here. Yes, we had squat gigs in the provinces but in London it was going on at scale. London also had easy access to the “big names”, which has always been one of those inherent contradictions of the Anarcho-punk movement: a leaderless cult with leaders, some of whom now command large fees to provide reminiscence and represses.

Whilst the focus is on anarcho-punk, David allows the edges to blur and provides context where a building had a former radical use or, like the Wapping Autonomy Centre, was shared with non-punk activists (spoiler: it usually didn’t end well). There is background text about anarchists and activists who were not punks such as the Black Flag editorial team (in Albert Meltzer’s case most definitely not a fan of punk), Stuart Christie, the Stoke Newington Eight, the Black Panthers and more. Of course, these people inspired some in the anarcho-punk movement who got seriously stuck into the propaganda of the deed. The fact that, for instance, the Brixton 121 squatted social centre, which carried on hosting some amazing gigs until its eviction in 1999 was home to the British Black Panthers in the 1970s including such luminaries as Linton Kwezi Johnson, Darcus Howe and Olive Morris gives the focus on buildings a psycho-geographical feel. “If those walls could speak” (those that haven’t been demolished, or worse… turned into an estate agents!). Thankfully David uses anecdotes from people who were there at the time to give life and flavour to the bricks and mortar. After all it was what went on inside that mattered, not the fabric of what could have been literally any building, which drives a coach and horses through the psycho-geographical approach.

Punk and non-punk alternative bands that were not of the anarcho persuasion get the odd name check as they sometimes played the same venues or, as in the case of Southern Death Cult or My Bloody Valentine, they featured former anarchos and squatters in their ranks. Anarcho gigs didn’t just take place in squats and community centres. There are pieces about specific gigs at well established venues such as The Brixton Academy, 100 Club, The Fulham Greyhound, Clarendon Ballroom (site of the famous psychobilly Klub Foot) and Hope & Anchor (admittedly whilst it was briefly squatted).

Anarcho-punk was always about more than just the music and the bands, but only a fool would pretend the bands didn’t matter, and David gets this balance about right. Class War’s action at the Henley Regatta in July 1985 has its own chapter and is a fun read, and Stop The City gets mentioned here and there, of course. A piece on animal liberation benefit gigs at the Blut Blut features an interview with Paul Gravett, who spearheaded investigations into undercover cops inflitrating the animal liberation movement in the UK during this period—and until relatively recently. The ensuing media attention led to the Spycops inquiry into the Special Demonstration Squad which is still running.

Among the extra content there is a piece about The Kings Head in Deptford. Conflict’s song “Kings & Punks” on their debut LP It’s Time To See Who’s Who was about this pub venue, where Mark Brennan of The Business promoted various gigs. The lyrics, missing from the inner of the album, are included here too. A little more focus on the early years of Conflict led to David visiting the site of early rehearsals and gigs in Eltham, making for another chapter.

The chapter about The Clarendon spins off into a recollection from Hugh Vivian of Omega Tribe detailing the band’s drift away from anarcho-punk and eventual break up. There is a run down of squats as locations and squatter punks as extras in the Hazel O’Connor film Breaking Glass. There is also a bit more focus on the technicalities—and pitfalls—of life as a squatter. An account from Irish punk lifer Conor about his experiences resisting the eviction of the mass squatted Stamford Hill Estate in 1988 can be seen as a harbinger of change, the end of an era, and fits well with the timeframe of this book. The freedoms that had been enjoyed were now under attack. The party wasn’t quite over, but it was being curtailed.

My takeaway from reading this volume is that it’s not just about looking at the past, it’s about celebrating it. There’s plenty of that going on these days, and it seems like even a supposedly forward-looking movement like punk is getting sucked into retromania at times. Reading about the vibrant culture and fun that was had, it is tempting to lament how it is now so much more difficult in a gentrified city where property is the number one commodity for Russian oligarchs, billionaires, and developers (and for those of us outside of London). We hear about venues shutting down all the time. Even if a site wasn’t snapped up and encased in steel by the money men, more draconian laws on squatting make it more difficult to occupy buildings for long enough to do much.

You can also see it in another light. Celebrating the freedoms that our tribe once had to develop and share counter culture should inspire us to try and create more spaces to do this sort of thing. While there are still occasional squats and gigs under motorway flyovers and social centres still exist like Bradford’s 1 in 12 and Brighton’s Cowley Club, the DIY punk community in the UK has had to engage in more permanent approaches to save spaces, even if we are now a minority interest alongside other communities and cultures. There are organisations like Music Venue Properties, who are using community investment to buy the freehold of music venues in the UK to secure their future. Anarcho-Punk: Music and Resistance in London 1977–1988 serves as a reminder of what we can release when we make that effort to create autonomous spaces.

Review by Nathan Brown for DIY Conspiracy.

Nathan is a punk rock lifer and has promoted DIY gigs, written and published zines and played in Haywire, Whole In The Head, Liberty, Armoured Flu Unit, Abrazos plus a few other bands.

Comments